Recording from Jan 3, 2024. Zoom with Larry.

Skiers and snowboarders in the Northwest are stoked for some snow...finally! Listen to Larry for info on weather in the Cascades and what to expect now that we have new storm cycles. Can we recover the snowpack? What's a Polar Vortex? How does the Convergence Zone in Everett make a difference for Mount Baker? And more...

TRANSCRIPT AND SLIDES

All right, it's all about what's been happening so far.

And what we expect in the future and the future is looking pretty good. In the past year December was not that pretty. You know, most of the ski areas are below normal snowpack.

In fact, all of them are. And we're going to go through that. What, what's going on with El Nino. Where might be places that you could go at this point.

And the best thing is what's going on in the short range forecast, that is for the next week. So Happy New Year, everybody, and welcome to the all Northwest years on this January 3rd 2024.

I’m meteorologist Larry Schick, the Grand Poobah of Powder, and that's me getting some tracks at Crystal a few years ago, just starting to get the hang of it then.

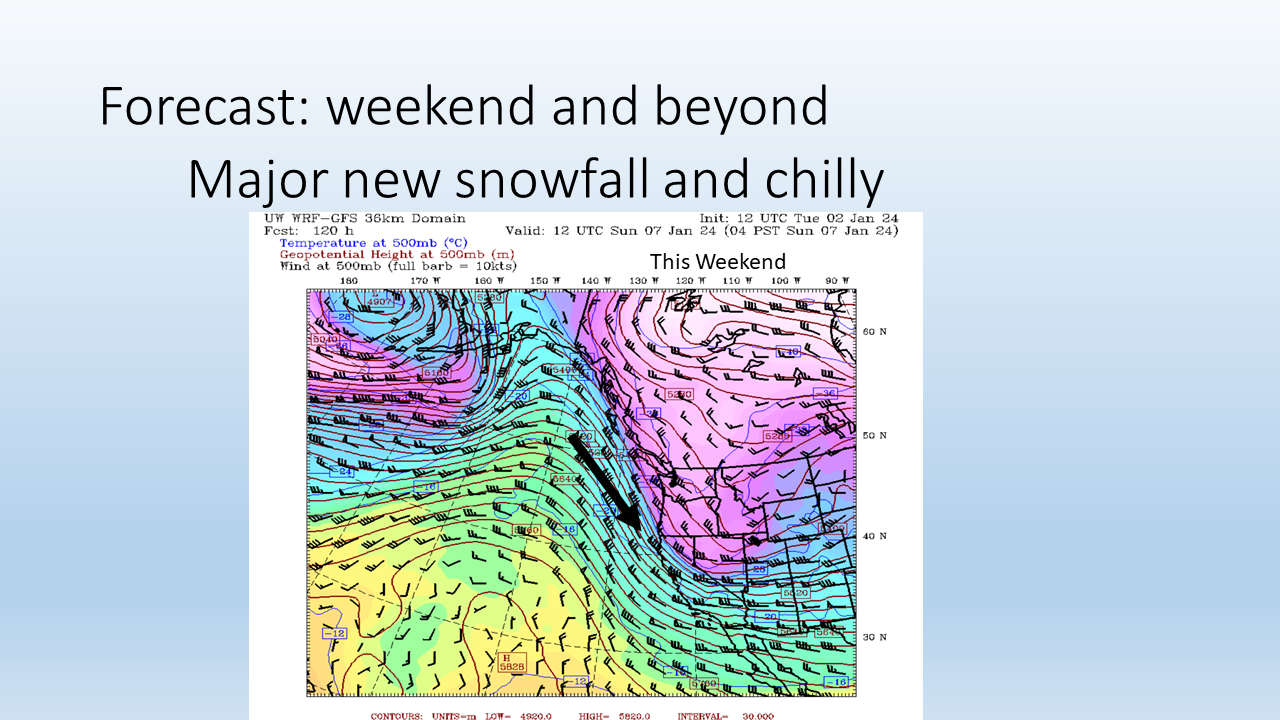

All right, onward to our first slide where we're going to talk about what the pattern changes. This is a big deal.

We've had this pattern of warm and wet weather but warm weather for much of December, but the weekend and beyond shows major new snowfall and chilly. What's changed is this upper level pattern. This is winds in the upper atmosphere coming this weekend, and there's some high pressure well off the coast, but it's backed off enough from the coast.

Here's Washington right here. This indicates cooler air here. So the air is coming down from the north, and this is a drastic change from much of December where the air was coming from the south and southwest from a warm direction, and that caused the above normal snow levels that we saw through much of December and even November as well.

And that's caused the snowpack to be below normal.

Here's what we're looking at. Okay, I'll just show the best stuff right off the top.

The next seven days, low snow levels and a lot of snow. So when I give a forecast, I like to kind of tell what elements of the forecast I have a lot of confidence in and what elements I have not as much confidence in. Because all forecasts are not equal. They have certain elements that we're really kind of sure of and other elements that we're not sure.

So let's go through them for the next seven days.

I have high confidence that we're going to see low snow levels, and that'll begin really over the weekend. And to some extent, they are down a little bit now.

So we'll have these low snow levels of cold and snowy weather pattern. Models have been really consistent, and you see this big mass of cold air up through B.C. That's going to be filtering down through our area and much of the country.

I have moderate confidence in the timing of these specific storms.

We have several in the lineup, but sometimes, you know, they might come a little early or a little later. So the timing can be variable. That said, I still expect all the storms to show up.

Sometimes they might go a little north, a little south. But this forecast you're looking at, this map with all the nice colors, the yellow stuff is like two to three feet of snow in the next seven days. And that's right over the Cascades of Washington, Oregon, and British Columbia.

And, you know, our sponsors like in the inland northwest, 49 Degrees, and Silver Mountain, they're going to get a substantial amount of snow as well, probably two feet of snow. So a lot of people getting snow. You can see it's widespread all through the northwest and even down into California.

But we're going to be sitting pretty over the Cascades and the British Columbia coast. So Whistler will be doing good. Interior BC will pick up as well.

Here's what I have low confidence in,…

and it's kind of early to talk about, is what's going to happen after we get this, you know, series of storms. Is it going to keep continuing? Is it going to stop and start, pause, or are we going to get back into the warm pattern? So that I don't know. I'll know more in about a week to see if it continues or not.

So those are some of the confidence levels I have in the storms coming up.

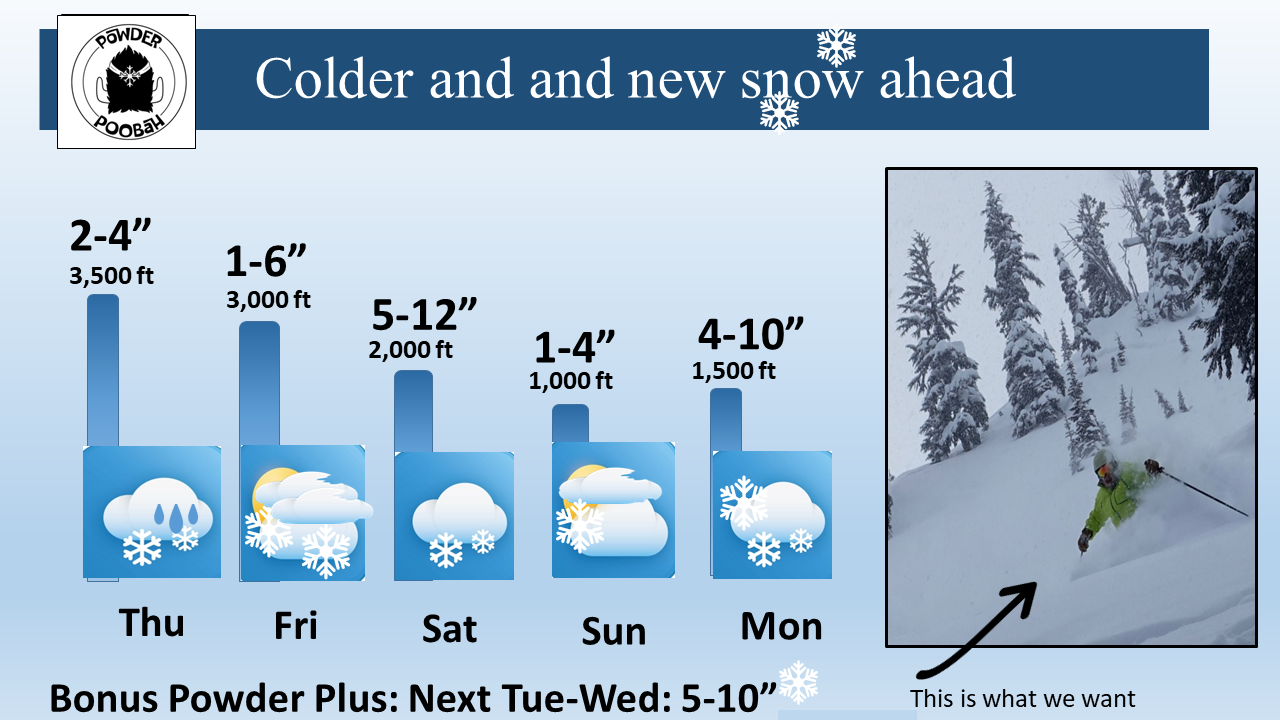

And here's the forecast for tomorrow. There's a storm coming in.

We could have maybe an inch or two or up to four inches. Snow levels at 3,500 feet. So some of the lower slopes might get wet snow or rain mixed with snow.

That's Thursday. Not a big deal on that storm.

The Friday storm, same thing, kind of not a big deal. Some lingering snow from Thursday storm.

I put the six inches because there seemed to be a convergence zone that might set up for Stevens. So the six inches would be the high end in the central cascade, Stevens, and maybe the summit.

But most areas might have just a few inches. The snow level is creeping down. It's the weekend that really starts to show the potential.

Snow level goes to 2,000 feet on Saturday, Sunday, and Monday, about 1,000 feet. Look at that snowfall on Saturday, 5 to 12, and then 1 to 4 on Sunday, and then another big shot on Monday into Tuesday and Wednesday. So more powder coming on Tuesday and Wednesday, too.

So a nice pattern. And this is what we want, finally. And I'm going to compare this to how much we have and how much we really need to get back to normal.

But this is a great start. We're talking 1 to 3 feet of snow, essentially.

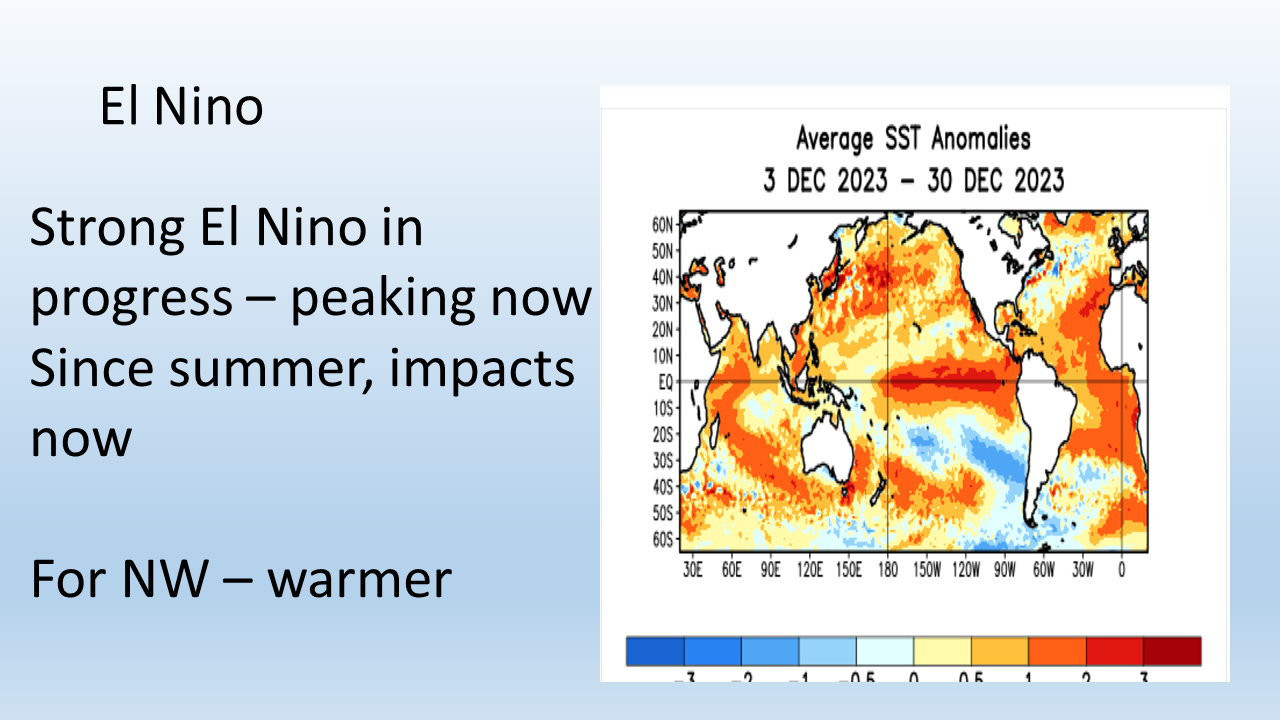

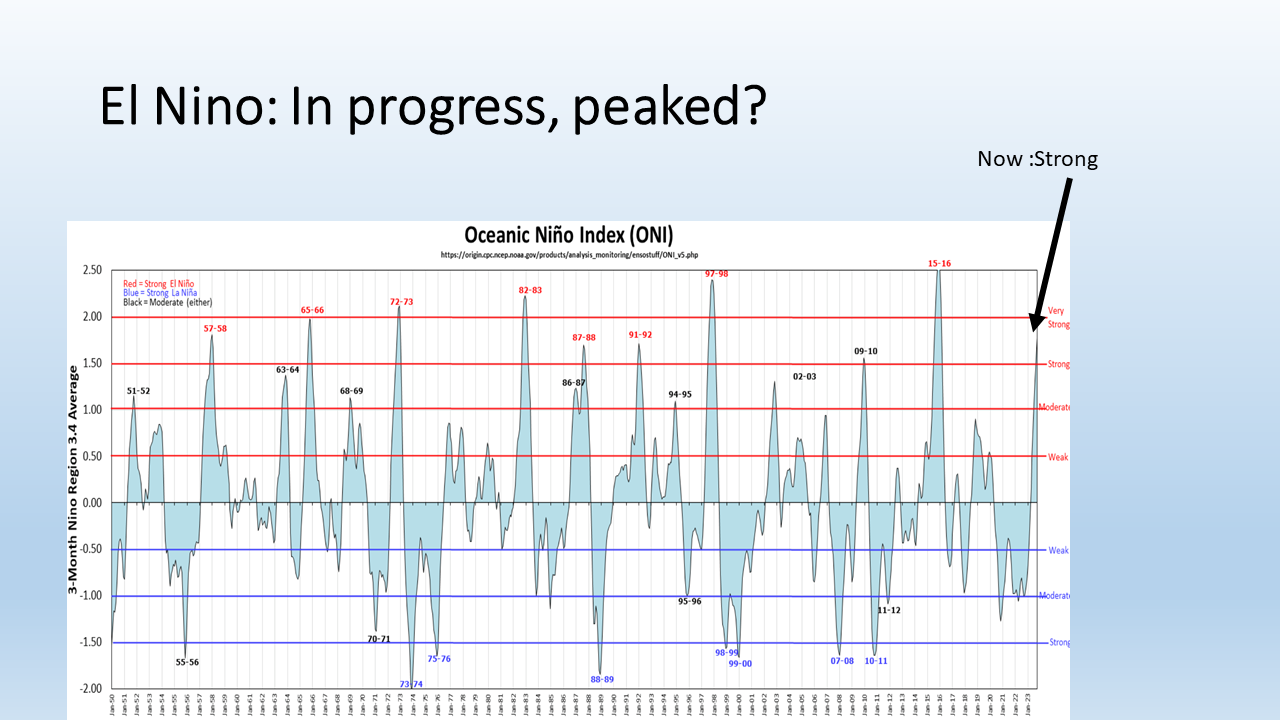

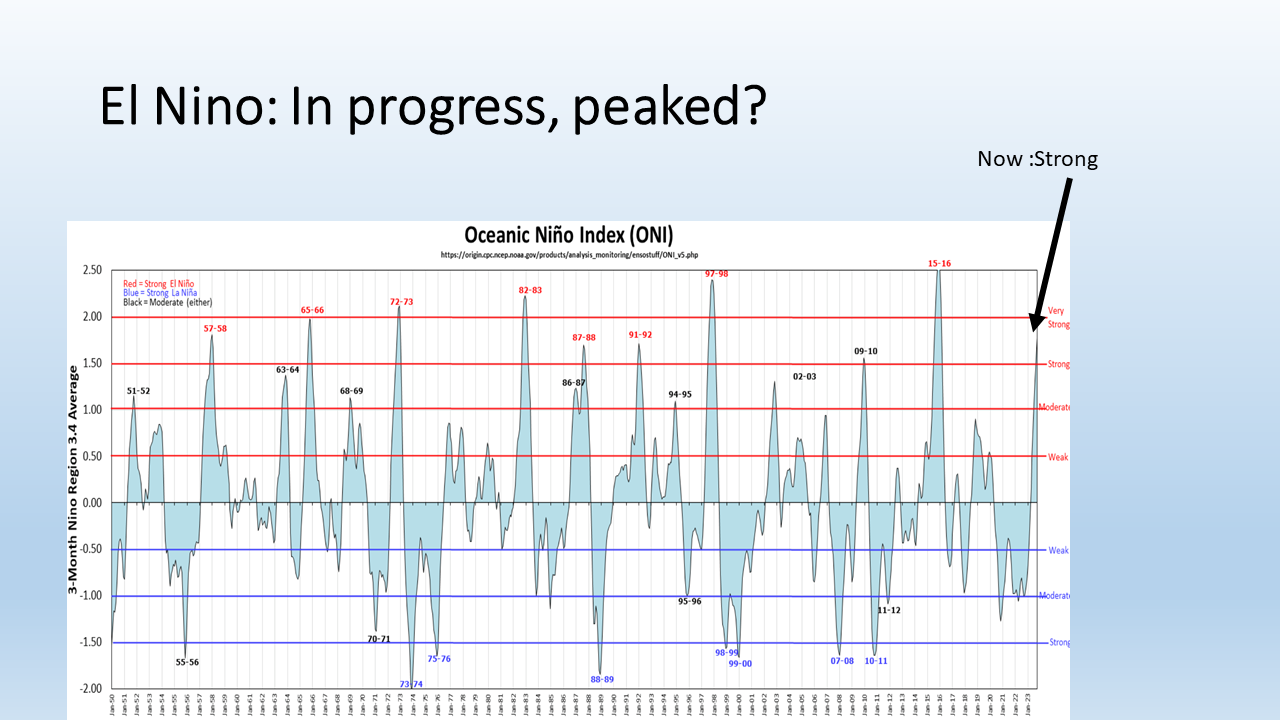

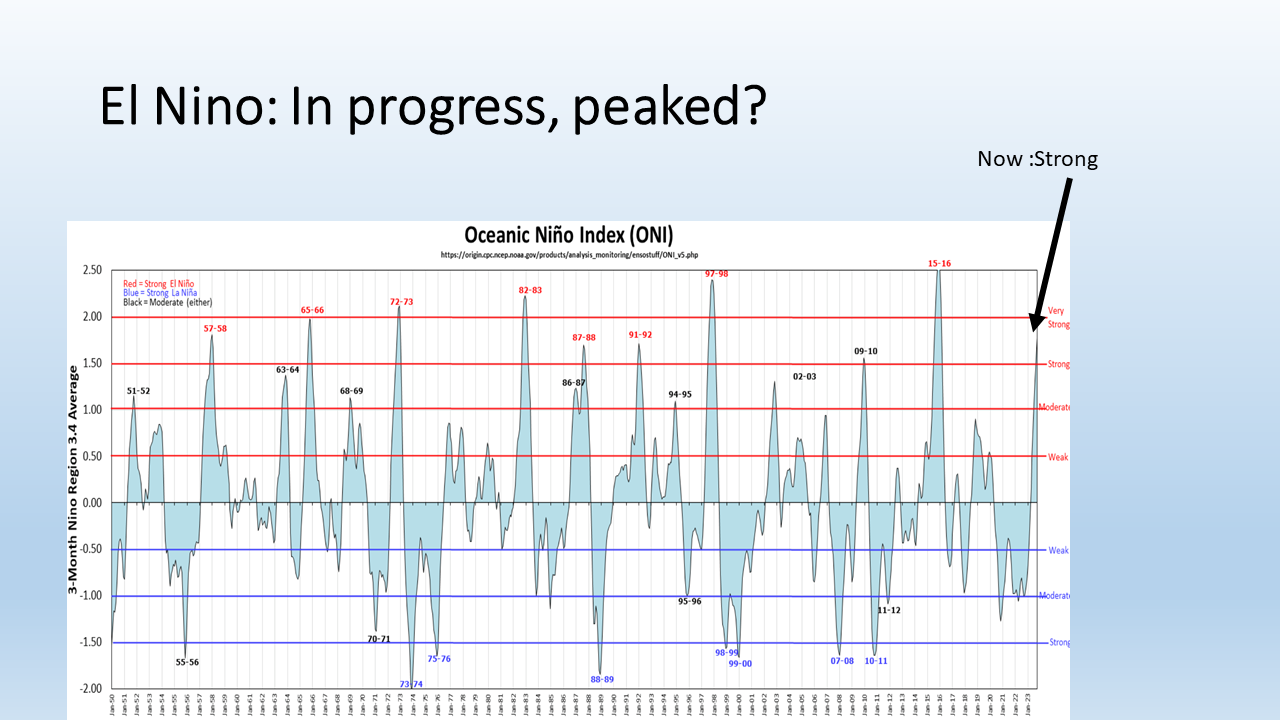

(4:57) We still have El Nino going on.

And we can tell El Nino is still going on because of this orange area out in the equatorial Pacific. This is what defines El Nino, this warm water pattern right here. And it's been going on now for several months.

But here's what people don't understand. El Nino's impacts don't really affect the west coast of North America and really all around the world until late December into January, February, and March. So we don't expect these effects quite yet, although we've had the warm part.

But part of the warmth is background global warming, but also look at the oceans of the world. Anything that's orange is above normal water temperatures. So the earth is kind of warm, certainly the warm water temperatures, but we're getting this big mass of cold air that's going to be shoving down into the central part of the country.

So the strong El Nino is in progress. It's peaking right now, and it's been going on since summer, but the impacts are happening now. For the northwest, the El Nino's generally mean warm, and that's what we've seen so far.

So some of the impacts may already be in effect, but generally speaking, the effects don't start to happen until late December into early January. And that's what we'll start to see. And remember, California should be getting wet, but they're really not getting that wet. They're below normal too.

(6:18) Here's the El Nino forecast.

The red bar graphs go up really high through January and February, and then it starts to ease up in March, as I said.

Notice it's going down, down, down. By next summer, it's almost gone. What seems to be happening is neutral.

We do much better in neutral. And then you can see on the right, this pattern also shows El Nino dropping off into the neutral zone. The neutral zone is between this 0.5 and minus 0.5. These are actual water temperature averages out in the Pacific.

So this is the neutral zone here. La Nina's down here. El Nino's above.

So this is a pretty strong El Nino event, definitely. I'll show you that in just a moment. We'll compare different El Nino events.

(7:02) And here's what the Climate Prediction Center is forecasting, given this El Nino.

Remember here, this is the biggest understanding. El Nino is not a dictator.

It doesn't run the complete show. It just nudges or tilts the odds in a certain favor, and that is above normal temperatures for the northwest and above normal precipitation for parts of California and the southwest. You can kind of see a suggestion of this with precipitation here and temperature over here, and that's the Climate Prediction Center.

These long-range forecasts are really difficult. They're very difficult to work with. That said, this is the best we got going, and we're going to have to deal with it here.

But you hear constant stuff on the news, oh, this is El Nino. Nobody says it's not El Nino, no matter what's happening. So I just find this kind of laughable to some degree.

(7:55) Here's what it meant in reality so far.

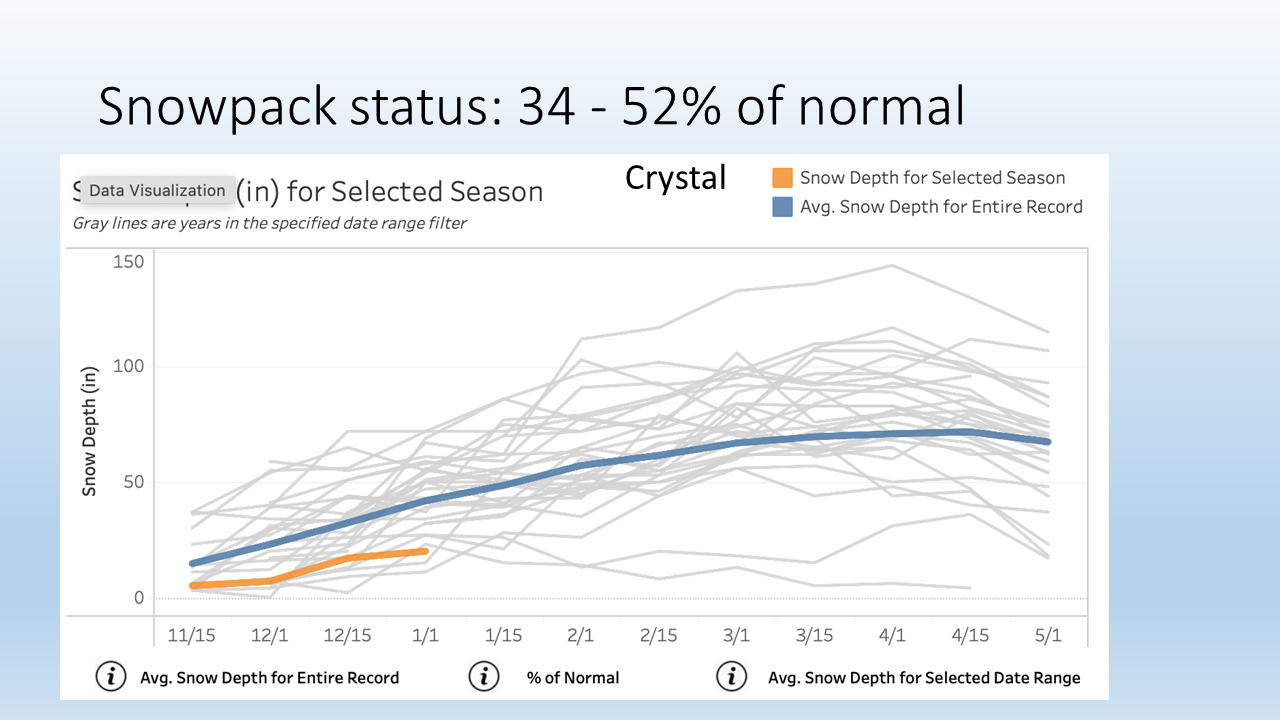

So I took Crystal. This is from NWAC's very good climatological site that graphs things.

So this is what it's been so far as of January 1, the snowpack. It's been below normal. Normal is the blue line.

This is what it's been. These low lines here, these are those bad El Nino years of 2005 and 2015. So some of these continued pretty bad, right? But wait a second.

Some of them go back up to normal. You can see them right here. See these? They go back up to normal.

So it's not a given that the rest of the season is a write-off. Don't think of it that way. It can happen.

But it doesn't give us a death sentence. These were pretty bad years, if you remember, 2015 and 2005. I remember those specifically.

But even the bad years, some of them kind of hang in, and then they kind of bounce back in the springtime here, too. These high ones, these are the good ones. La Nina, 1999, 1140 inches of snow at Mt.Baker. That's the big one up there. Of course, Crystal had a good year there, too.

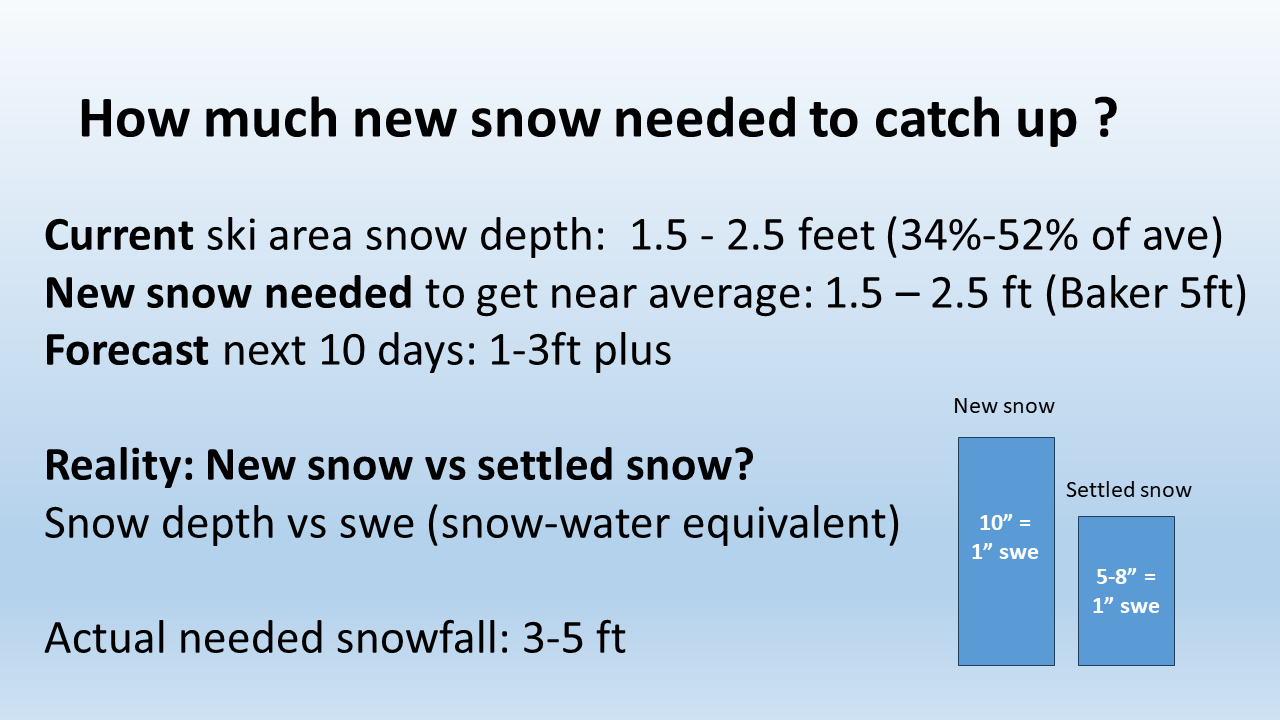

Not quite as much snow as Baker. But that just shows you what the status is. Currently, the snow pack is 34 to 52% of normal in the ski areas.

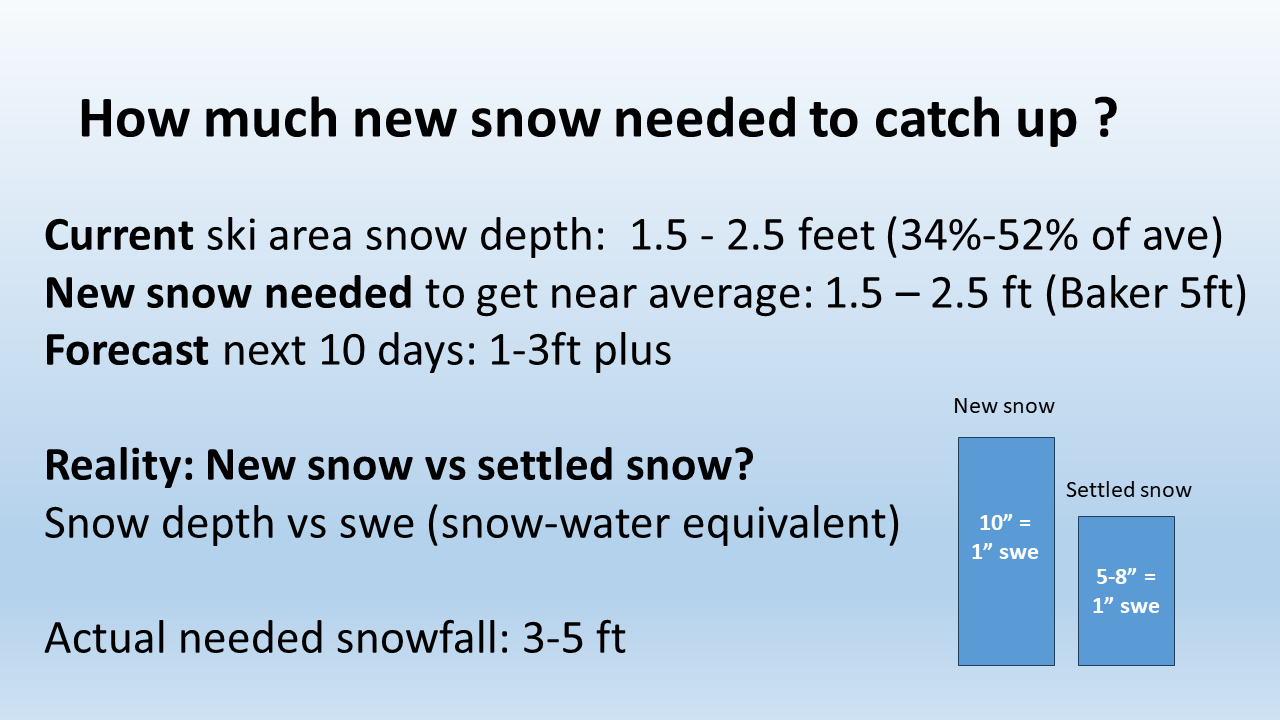

(9:20) Now, we're going to go through a little thing here of snow depth versus what's called SWE. That is the snow water equivalent. I'll tell you what the difference is.

We'll tell you that in a moment. Here's what it is in a broader sense. This is beyond the ski areas.

This would be taking different elevations from about 2,000 feet to about 6,000 feet. You can see the Olympics are really hurting for snow. Cascades are well below normal.

This isn't the lowest on record, but it's getting in the top five lowest on record. And east of the mountains, similar setup, too. And you'll see that we're not alone.

We are with much of the west in that sense, too.

(9:47) So here's an interesting thing. I did some work here.

How much new snow is needed to catch up? Currently, we have about a foot and a half to two and a half feet. And it's 34 to 52% of average. How much new snow do we need to get near average? We need another foot and a half to two and a half.

Baker would need another five feet. And that's new, fluffy snow. The forecast in the next 10 days is one to three feet.

So that ain't bad. But you've got to remember, there's a nuance here that people never consider. The reality is what is new snow versus settled snow? When you get new snow, it's roughly 10 inches equals one inch of water equivalent.

So if you melt it down 10 inches, it would be one inch of water. But it takes a couple days and snow starts to settle. So you still have the same snow water equivalent, but it settles to five to eight inches.

So the depth settles. And so that can be a difference. And it still covers things, but it starts to settle.

And so be aware of those differences when people are saying how much snow they have, either at the ski areas or in general. There's new snow, which can be quite impressive because it's nice and fluffy, has a lot of loft. But then it settles after a few days or a week or so.

But it still has the same water content. So we actually need of new snow, fluffy new snow, three to five feet to get back up to normal. But so what? We're looking at one to three coming.

That's not bad. So we're going to be improved. So expect that. It will be improving.

(11:20) I want to go through real quick the atmospheric river we had about a month ago because it was a fascinating little thing.

One of the things people don't understand is what happens to the snowpack when we get these atmospheric rivers.

The snow level goes up. You know, it goes up well above 6000 feet. Most of the Cascades get rain on snow.

So here's what happens. So let's look really closely at what happened here. And so this is normal, the green.

This is what happened so far. So we were tracking actually this early snowpack. It was pretty close to normal.

Then it kind of flattened out in late November. And then that weekend before the atmospheric river, we got quite a bit of snow. You can see it there, right there climbing.

And then here's where the atmospheric river hit, right there, that little bump. It goes down. And we lost.

So we lost some snow. But it doesn't erase the whole snowpack. This is what people don't get.

If you look at it really closely, I got it on the right here. So there's where my pointer is right there. We got snow before the weekend before.

Then we got the atmospheric river. We lost some, about one inch of snow water equivalent. And then we immediately gained it back in the next few days.

And so we totally didn't lose all the snowpack by any means. It definitely consolidated. It definitely beat it up.

And then the problem is it just hasn't snowed or it's been just rain, no snow. And just recently we got a little snow. So you can see that.

So now we have about eight inches of snow water equivalent. We should have about 15. So we're roughly half.

So we need quite a bit of snow. You can see at the max at this elevation, this is pretty high, 6,000 feet. But the max we get 38 inches of snow water equivalent.

If you want to times that by three, or more than that, it's really, that would be about 50, it'd probably be about 70% of that deep. So anyway, it's a lot less than the actual depth of the snow is what I'm trying to say. Snow water equivalent is how much water.

If you took that depth of snow and you melted it down, that's how much water is in. But it gives you, it's a good proxy and approximation for the snowpack. All right.

I just had to talk about that because it doesn't, these atmospheric rivers do not melt the whole snowpack. They will melt several inches of it. Yeah.

But they won't melt the whole snowpack. It doesn't happen. I've been up there a bunch of times, it was raining.

It melts a little, but not that much. Okay, settled. All right, because I saw the national television people, local, they don't get it.

They think the floods are being caused by melting snow. Only 10 to 20% of the, is snow melt that's producing those floods.

(14:02) All right, so seasonal forecast is difficult.

La Nina generally treats us pretty good. We know that from the big years. El Nino does make it difficult.

And it plagues Northwest skiers with some warm temperatures. That's usually the problem. That was a problem in 2015.

We had normal rainfall, but we had well below normal snowpack. And remember, snowfall happens in storm cycles. This is one coming up.

This is a storm cycle and we can see them coming. The models handle them very well. We can see this one's got a lot of cold air, so I'm not worried about ice, snow levels.

And so that's going to be good. And remember, one month snowfall or lack of does not translate to the next month. It's a good example of what's going on right now.

So you can't tell what's going to happen next month by what's happening right now and vice versa.

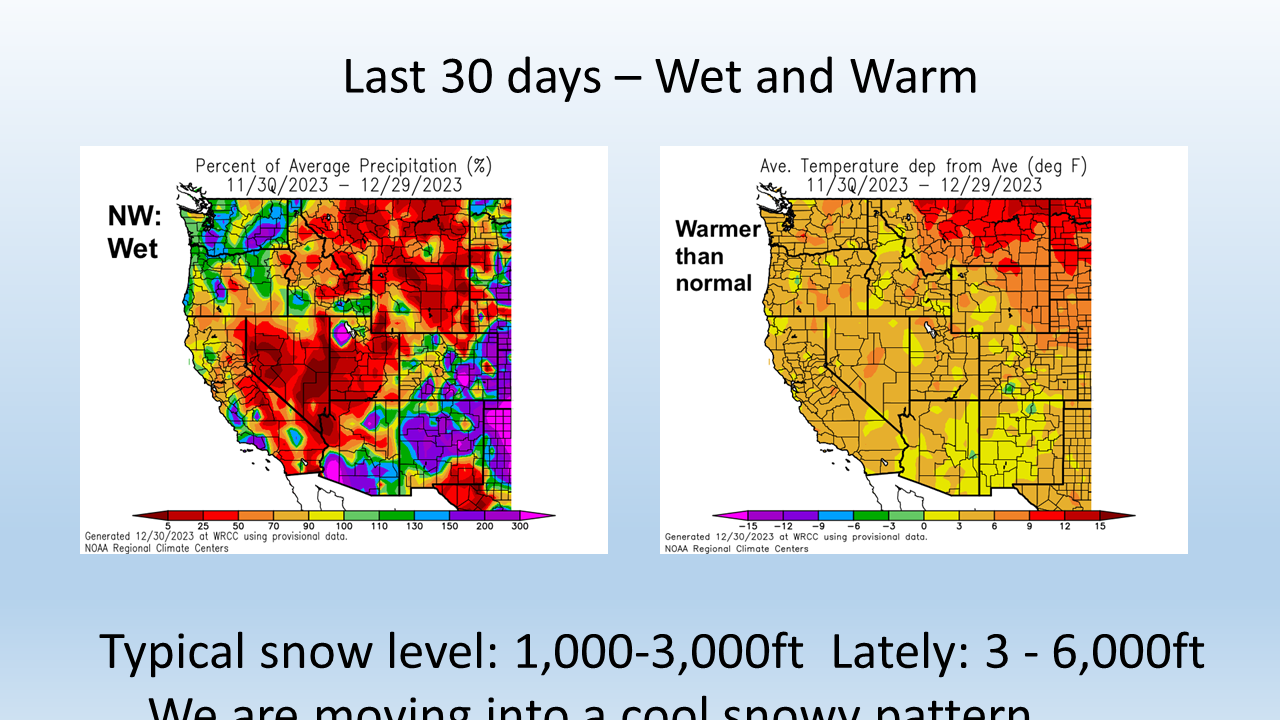

(14:50) Here's another interesting graph here.

For the last 30 days on the left is rainfall or precipitation, I should say.

So you can see the Northwest, this is above normal. The blues and the purple, above normal, even in eastern Washington, parts of Oregon. Most of the West, below normal.

Okay, a little bit of the coastal California, but most of the West. And look at the temperature on the right, warmer than normal all over the West. So lots of the West has been plagued by warmth and especially lack of precip in general.

Look at parts of Utah and Colorado's done all right. It's kind of a mixed bag there. But so typically the snow level this time of year would be 1 to 3000 feet.

But lately in the last few weeks, it's been like 3 to 6000 and went even higher than that during the atmospheric river. But we're moving into this cold and snowy pattern.

One area I was asked this question, what area has gotten near normal? Grand Targhee, you know where that is in eastern Idaho.

It's actually in Wyoming, but you have to access through Idaho. That place does really well under a variety of conditions and they are almost 100% of normal snow. So is Steamboat Springs, they're close to normal.

Most of the West, interior British Columbia and Whistler, they're below normal. But they'll get in a lot better shape in the next couple of days, really by the weekend and beyond. So everybody's going to be on this improving weather.

It'll help everybody as you saw in that one graphic. But we're going to especially get help here in the northwest.

(16:27) All right, let's move onward here.

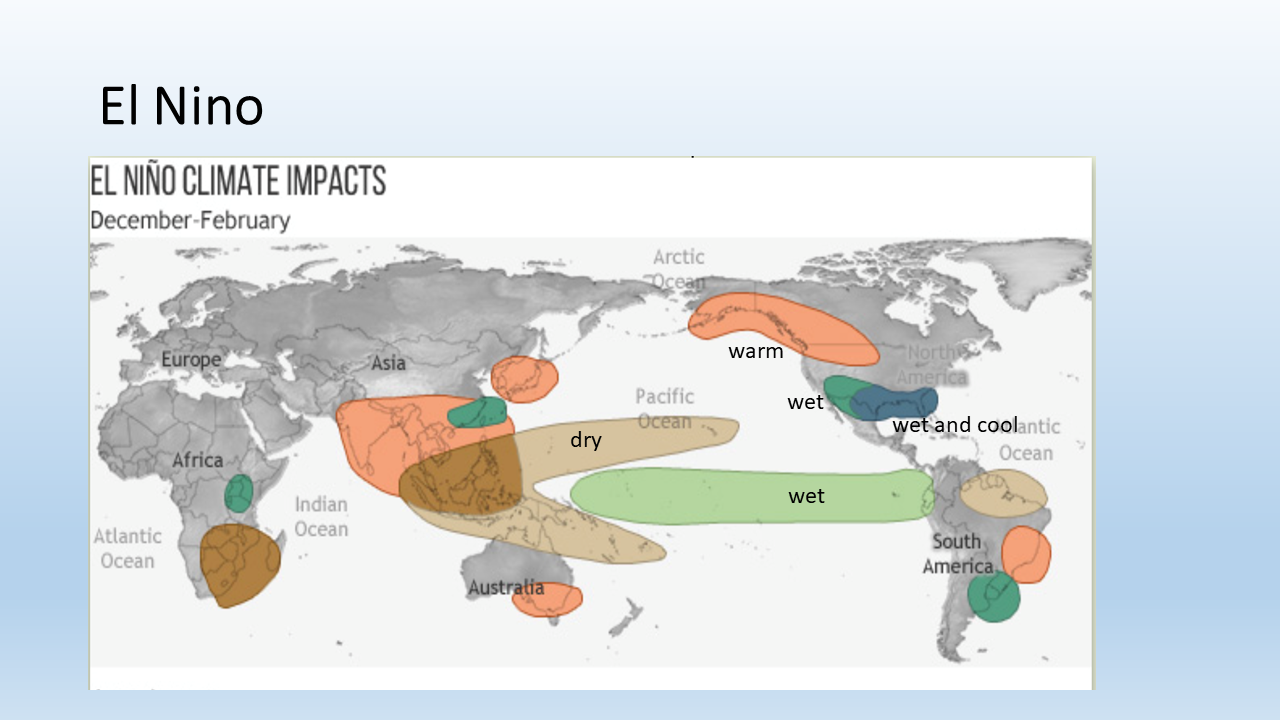

This is the climate impacts for El Nino. Remember, here's another thing people get wrong all the time. Europe's bad or good because of El Nino.

Well, look at this. It has no effect on Europe. No impacts.

All right. Get that right. I hate this people say.

Even like Tahoe, no impact from El Nino. No, let's put it this way. No predictable impact.

There is an impact for southern California and the southwest for wet and cool down here and the warmth up here. And then wet in different parts of the world. So it's really indifferent to a lot of places.

And so that's important to note that our current situation, we've had normal precipitation, but it's been warm and that's been the problem. So whoops, whoops, whoops. I went too fast.

(17:19) I have a really good slide there. Hang on. All right.

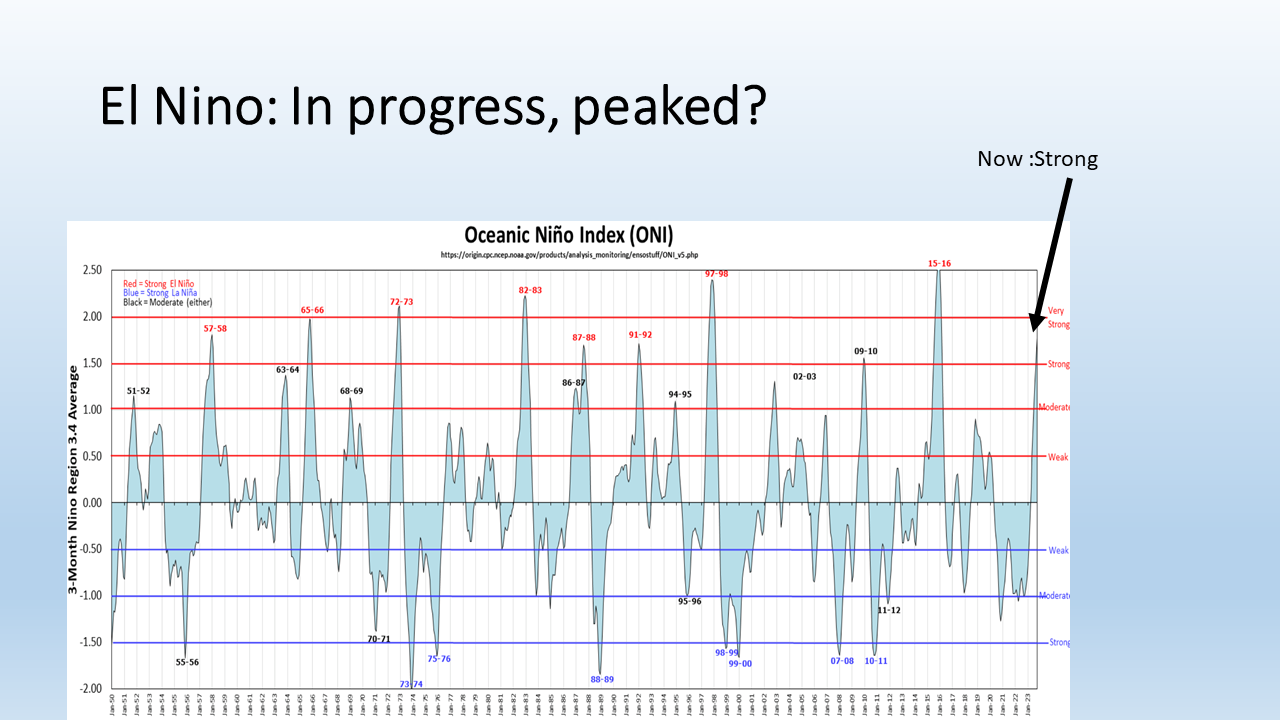

So El Nino, it's in progress. It's I think it's peaked. You can see it right there.

The big arrow on the right. You can see the one in 2015-16 was higher. The one in 97-98 was big too.

82-83. Now that one was a classic. Everything was very predictable.

So after we saw that one come through, oh, this is great. El Nino can predict all this stuff. Well, it's not as good these days.

And so a lot of people, a lot of scientists I've talked to are second guessing this. I went to a class called Scripps Institution of Oceanography, and a lot of people are doubting it now. It does always occur on a different background.

And maybe with global warming, it's going to affect it differently. So it doesn't have even in its best, it was still only nudging. So anyway, you can see it goes back and forth.

This is that big year right here where I'm pointing at the bottom. This is the La Nina year where we had really consistent great snow, especially in February. And that was a big La Nina year.

So every time I see a big La Nina year, I get really confident that we're going to have a good year. And typically we do. It's cool and it's wet, and so we get good snow.

All right, so you can see how it oscillates back and forth. And so next year is kind of looking toward at least neutral, maybe La Nina. So this El Nino is not going to last.

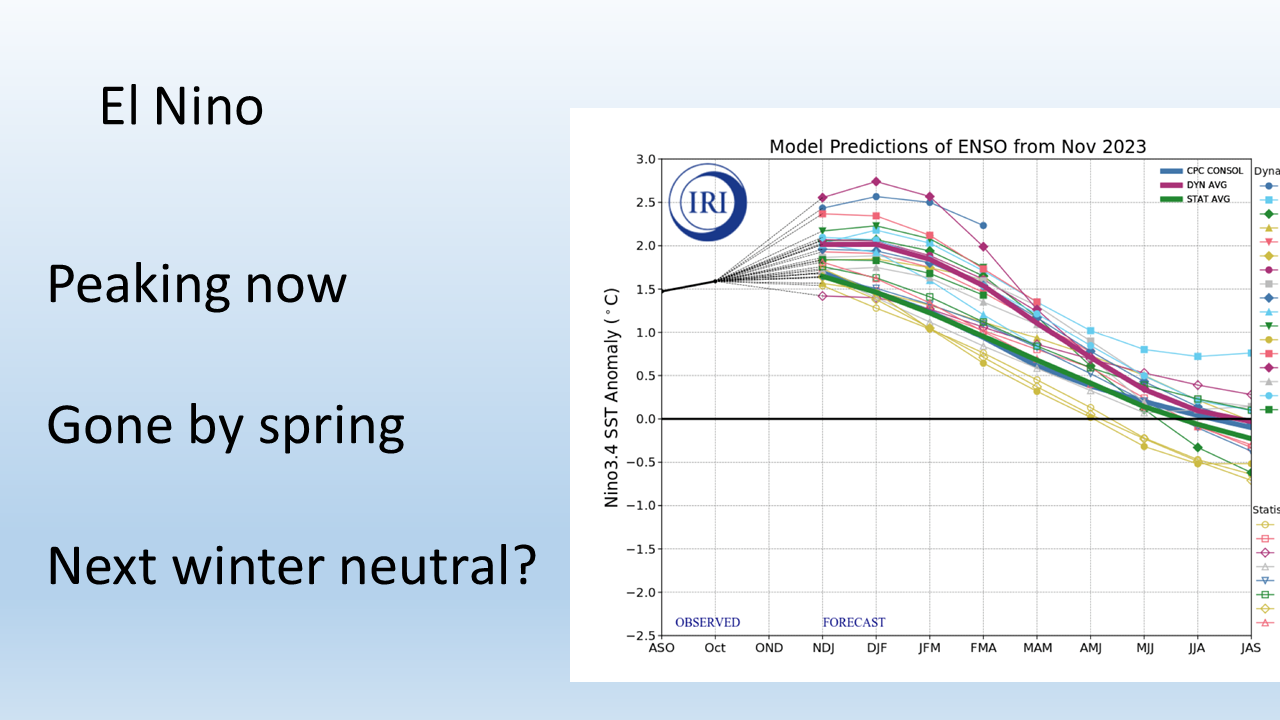

(18:39) And this prediction model shows that too. So this is, let's see, this is about right now. And you can see it's peaked, it's going down.

And this is in March. It's going back toward neutral is about right. So neutral is beyond the ski season right here.

It'll be in the spring. So if you're thinking about spring skiing, you know, backcountry or inbounds, it might kind of turn nice and could get some fresh snow. And then we go neutral for the summer.

And then it looks like to me, extrapolating, it goes to neutral or La Nina next year. All right. That's a lot of speculation.

(19:13) Okay. We had a couple of quick questions. I'll go through and we'll answer all your questions on chat.

Enter them in chat and Andrea will tell me. So somebody said, I'm going to Mount Hood in two weeks. What do I expect? Well, given this pattern the next week, I'd be very optimistic.

You know, I don't know what it's going to be like in two weeks. Here's another thing on long range forecasting. You know, we only know about with confidence two to five days, maybe seven in the most.

By the time you get beyond seven, it gets really fuzzy. And so, you know, don't take those kind of forecasts to heart too much. Now, sometimes I've seen forecasts that I can, I've done a 12 day forecast, nailed storms and stuff, but that's rare.

And it was a bit of a guess. Somebody's going to trip to 49 Degrees. One of our sponsors, great spot and Blewett over by Walla Walla.

49 degrees is near Spokane, north of Spokane. And I would expect conditions to improve greatly by February. So that's good.

This is a continuation of a question that we had last time on where to build your cabin. They wanted to know about interior BC, Sun Peaks versus Revelstoke. Sun Peaks is in a little bit of a snow, lesser snow area because it's kind of blocked from the coastal storms and doesn't get as much as the rocky storm.

But on the other hand, the snow quality is really good there. So they don't get quite as much snow as Revelstoke. I mean, if you're going to build your cabin, go to Revelstoke, I guess.

And that's it for those questions there. Let me see if I got, oh yeah, people wanted to know about Europe. You know, I heard they were doing good earlier in the year.

I don't know what they're doing right now. People want to know when is Alpental going to open? Well, you know, I think they need more than a foot there, but it'll help if they get the two or three feet that we expect, that would probably get them open. Let's see, that's about it.

Silver Mountain, we had a question about Silver Mountain, one of our other sponsors, and I'd say that also is going to be improving here in the next week. They'll get a lot of the snow that we're getting here on the west side. So I'm happy to say they'll be much improved as well.

(21:19) And so that will wrap up the forecast and everything else for now. I'm very optimistic. Let's see how this goes.

Like I said, I'm confident we're going to get new snow. How much? I'd say on the high end of one to two to three feet. And so very confident that I'm confident the cold part of it too, cold part of the equation.

It's just like when the individual storms come in. I think Saturday is going to be good stormy day. I think Monday and Tuesday of next week will be stormy in between.

Not as much, but still quite a bit. And then the question is what happens after the middle of next week? Not clear on that. You know, get it while the getting's good.

That's all I can say. But thanks very much. Whoops, that's it.

So I will open it to questions

(22:11). Thank you, Larry. So Evan asked a few slides back, right before the seasonal snow forecast slide.

Is that consistent across locations, wet and dry, Corral Pass being in a more dry location? Okay.

Yeah. So that's a really good question. So yeah, I'll get to the Corral Pass thing.

So Corral Pass is up near Crystal Mountains between Crystal and well, it's closer to Crystal and it's pretty high elevation, 6,000 feet. Whoops, I'm sorry. Sorry gang, I'm trying to find that slide.

Where is it? But it's a really good question he has. Okay, here it is. So this is a SNOTEL site, which is an interpretation site.

And so the question was, was this consistent with all the SNOTEL sites? And yes, it is. So this is a pretty high one. In fact, it's the highest one.

But every one I saw, now some, here's a couple things. All of them lost a little snow, but some of them that were really, they're lower elevation, so they didn't have much to start, they went down to the ground. Okay.

Whoops. So you're right in that, but everyone did lose a little and gained a little. But if you were another site that was down here that only had maybe an inch or two of snow water equivalent, you probably lost it all.

And so, but the consistency was this pattern that occurred when the atmospheric river happened, you know, it was like five to eight inches of rain on top of snow. But so yeah, it did occur. But like I said, some of those really low elevations, they didn't have much snow to start with.

And so yeah, they lost everything to the ground. And that's exactly what I see all the time. If you don't have much, if you only have, you know, a few inches or six inches of snow on the ground, yeah, you're going to lose it all if it rains eight inches.

Here's a thing. When somebody says, oh, it's the rain that's melting the snow, always ask them, how much snow melted and how much rain did it take to melt that snow? And you're going to, they usually don't tell you the rain. It's usually three or four times as much, no, five times, 10 times.

It's unbelievable. One time somebody got me in a conference, they said, well, this snow tell site, it lost 10 inches of snow water equivalent. I was like, wow.

And then I went and looked back and it took 30 inches of rain to melt it. Come on, that's what, that's what caused your flood. So, so that's, that's the deal.

(24:58) Now, Cindy wants to know how is Colorado doing? So Colorado is, is kind of a mixed bag.

It's doing okay. Steamboat I've heard is good, but generally speaking, they are well below normal as well. So, you know, they have snow making there, but no, no ski areas are doing great, except for those two that I picked out, Steamboat and especially Targhee, you know, are near normal.

So everybody's below normal. Utah's below normal. Most of Colorado, a little bit of Southern Colorado is doing okay, but just had a friend ski Telluride about a week ago.

And he goes, oh, there's only 25 inches, 22 inches or something, but they're going to get some more snow coming up this weekend too. So remember they'll get some of these storms too. So California, Colorado, Utah, for you travelers, they'll be improving as well.

Not as much as we will improve though. Just fine. Okay.

(25:50) Mike wants to know, do you think the El Nino index is very reliable this year since the entire North Pacific is warmer than normal? And then he says there isn't as much temperature difference and perhaps that will result in different weather patterns.

Well, so the El Nino, as far as it being an El Nino, it's an El Nino. There's no ifs, ands, or buts about it.

You make a good point that we've got some very warm temperatures around all the oceans of the world and the North Pacific, but the UW did some modeling a couple of years ago. And what they did, it was very, very creative. They were trying to understand how the water temperature in the North Pacific, how it might affect the weather.

Because remember the blob a few years ago? Okay, that was a big deal. So what they did, they modeled the weather, but they cooled off the ocean temperature and essentially eliminated the blob in this experiment. And they found that it really didn't affect the weather that much.

There was some cooler weather along the coast. So the warming in the coastal areas, there was a little bit of warming from that warmer water, but it didn't affect the overall weather pattern. So it really convinced me that it really didn't make a difference.

These weather patterns are just so huge and random that even El Nino can't do the trick all the time. Look at this. I mean, how much more warmer can you get? Not much.

And it's still not doing the trick. This pattern coming up in the next few days is decisively La Nina like, not El Nino. So that just shows me El Nino sometimes doesn't influence at all.

(27:39) What does this mean for forest fires this summer?

Yeah, hard to say. So forest fires, you know, there's different types of fires. There's the forest, the full on forest.

There's the grassland fires, which is the low, you know, brushes and grasses and that sort of stuff. So there's different types of fires. Some, you know, certain wet winters will grow more that low level grass, make us more vulnerable.

I think that since El Nino is done by spring, that that will go back to, you know, near normal temperatures. Remember, all our summers are dry. All our summers are warm.

It's just a matter of how warm and that transitional month months. That is the spring. What does that look like? So, you know, with El Nino kind of phasing away, you know, you can't forecast anything but kind of normal in the spring.

So I don't know what to do with the fire. I don't think it would, were that were that unusually vulnerable. We're always vulnerable, of course, because it's dry.

Every summer is dry here. You know, even the wet summers are dry. It just doesn't rain that much here.

So, all right, that's, that's my thank you. I'm not a fire expert guy. I'm a hydrology guy.

(28:59) Karina wants to know any predictions for Utah and Salt Lake area resorts?

Well, I mean, I think in the next, yeah, in the next week, they're going to get snow and a lot of it. But after that, they're also starting in the hole, just like we are, right? So my prediction is great if you're leaving tomorrow.

And for the next week, I think it'll be much improved. But remember, everybody's got a little snowpack. So you got to get the regular stuff covered, too.

You know, the off piste, you're going to run into rocks if you only got six to 12 inches of snow on top. But they're going to be, it's going to be improved with grooming and everything else. So, you know, go.

I mean, I never tell people don't go, you know, it's stupid. No, I think you just stay home and watch Jeopardy.

(29:47) Josh asks on the season 97-98 Tahoe had a record year, not El Nino influence question mark on jet stream over the Sierras the whole time.

I think 97-98 was El Nino. So I think I've got it on my I think that was an El Nino rule here. So here we go.

Here's see 97-98 was huge. See it up here where my pointer is.

Josh: my question was, I knew it was an El Nino year, but you said that Tahoe doesn't get influenced by El Nino. So that's what I was curious.

Larry: Oh, I see what you mean. Okay, so here's what I'm here's what I'm saying. So that's a really good distinction.

So, if you take all the El Nino years, all the years, there is very little nudging of the snow pack. From El Nino to Lake Tahoe, that is the central northern Sierra. So yeah, you can still have a this is the point, you can still have a big year in El Nino or not El Nino year.

Yeah, but is it driving it. That's another question. Here's a good example, Josh.

Last year, La Nina, pretty strong one, California, everybody's going drier, worst dry, we're dead, had one of the wettest and snowiest years on record. Okay, so there you go. I mean, what I'm saying is, how predictable is it, you know, I'm not saying it doesn't happen.

It's just how predictable it is. So I'm looking for ways to predict something off El Nino, and that's what I find lacking. And that's what the statistics shows for Lake Tahoe too.

So yeah, you can have it, but it's not predictable. So far this year. So far this year is a good example.

It's a dud.

(31:44) Hubster question: you mentioned that Europe is not affected by El Nino, but any thoughts generally on what the season might be looking like in the Alps in mid February.

Gosh, you know, the only thing I can tell you is, don't book anything until there's snow on the ground, but I think there's snow on the ground now, right? I think February and March are the best months to ski just about anywhere, because if you don't have snow by then, you're never going to have it.

And so, but if you do have an average year, or even a below normal, it's going to be about the best it's going to be right during February and March. So, you know, I'm not telling you to stay home, go.

(32:29) Okay, someone missed the start of the Zoom. Yes, this will be the recording and the transcript will be available by Friday. I hope to get it done and uploaded tomorrow. And there's a link.

(32:54) Becky asks, what is a polar vortex and how does it impact the ski season?

Okay, so the polar vortex, there's another one that gets blamed on El Nino or the polar vortex or some other big name.

So here's what the polar vortex, I'm going to try to distill it down because it can be quite complex and a lot of different levels. There's kind of an upper level one and lower level one. But so think about it this way.

Okay, up in the North Pole around the North Pole, it's cold, right? We all agree on that. And what happens is the winds that circulate around at a certain level in the atmosphere around the poles, and maybe, you know, you know, 60 or 70 degrees north latitude, they kind of go in a circle. And so then what they do is they corral that cold air around the North Pole, they corral it, right? So you think of them whipping around there, and they corral all this cold air.

And then once in a while, what happens is, and that's the polar vortex. Once in a while, the polar vortex starts to oscillate. And these lobes of that colder air sort of perturbed down to the continents, maybe the US like this might happen next week with the cold air happens over Europe, I think it's happening over Europe right now.

And so these lobes of air come down, and they pull this extraordinarily cold air down with it. And those are what caused these really cold waves during the wintertime, extraordinarily cold. We're generally protected by those because we have the Rocky Mountains and the Cascades sort of as a barrier, but it kind of slides into central part of the continent.

But the polar vortex is this corralled area of very cold air that sometimes lets loose in these, these lobes that come down periodically. And they can push quite far. Some of them have been responsible for like snow in Southern California, when they really get going and really push south, you know, this time of year.

It's rare, but that's what produces snow in Southern California, some of some colder. So we're going to get a modified version of that here coming up. But the central part of the country might be much colder.

Does that that's a polar vortex. Don't be afraid. It's just weather.

(35:06) Jay and Dorothy are asking, you can identify this weekend as a storm coming in. Can you see three to four storms in a row that would cover three to four weeks away, even though storm detail may not be predictable.

Yeah, you know what I'd like to do here.

See if I can grab. I have to go to a different screen. And I hope I don't lose you.

If I do, I can get a different screen up here because I've got this ready to show. Hang on just a sec. No, it's not gonna do it.

I get different screen up. Stop video. Would that do it? Would I lose everyone? I'm afraid.

I'm afraid. Yeah, I'd like to pull up this model because if I can show you this model, it would, it would show me how to do this. Let's see.

I could just get out of here. Get back into my Desktop. Boy, I'm gonna try it real quick.

Hope I don't lose you guys. Now I'm gonna, I don't see how to stop share, pause share. How about that.

I'll share that might do it. Your screen is stop sharing. I'm gonna resume.

I don't know how to get to my favorite screen but You know, on the model, it shows several storms. Now, I wish I could share this because it shows how sometimes they weaken. Sometimes they strengthen and and remember we get these models done about every 12 hours.

So sometimes this is why we change the weather. Sometimes the models, the The storm weekends and splits apart. We had a lot of splitting going on in December, because it ran into this high pressure that was over the continent and I ran into a wall.

I just kind of Squeezed apart and now it's shifted around. And so they're not falling apart. And so we're going to have the same kind of sequence of storms, but they're going to stick together.

Some of them are still going to be a little bit weak, especially initially like tomorrow and Friday, but once you get the weekend next week. And hold together and push inland and everything. So we have a series of probably let's see 12345 storms in the next seven days.

Some of them are weaker than others. And here's another thing, you know, we don't know what they're going to be like until we get really close to them.

We have a sense I have such a sense of it now because the models been consistent. I can see this pattern. It's not like it's going to change to something else.

So it's cold enough and it's consistent. Any more questions. Yep, yep.

(37:48) Which weather model do you prefer for mountain weather forecasting euro GFS or icon and how does a meteorologist build a forecast comparing various models and giving more weight to one or another.?

It's very difficult. And you're right. That's how we do. We never know. Here's the problem.

You never know exactly what models going to be right. Let's say your models right you know every day in the last week. But we don't know if it's going to be right tomorrow.

You know, that's the problem with models. You don't know. Now in the extended forecast beyond maybe three or four days that European model seems to be better.

But here's, here's the technique. Now that's being used. It's called ensemble modeling and what it is, is you take the initial conditions and you run maybe 10 different models off that and you see what the averages are and you see what the extremes of those averages are and that gives you bookends to see.

Oh, this model says six inches inches of snow, but it also shows Another run of it shows one inches. No. And, but the average shows for and so you're, you're very biased toward what the average of these ensembles Are and so that's what because they've shown the research has shown that that's the best way to forecast.

The best way to forecast is not to see what models been working correctly. The best is to stake all the models and run them all and see what the average is.

The average is better. It's like the consensus of a lot of smart people. It's going to be better than one person.

(39:38) Here's the problem. And I saw this working for the Corps of Engineers when we did flight control.

Guess what, sometimes in the very low end and the very higher end the ensembles don't catch it. So even the ensembles can be wrong. And I saw that and I had to be careful that you're running a big dam and there's a lot of water and a lot of thousands of people, you know, you didn't know when you were sleeping during the 10 years ago, I was running these dams with these people and we were, we were watching the models, but we had to be extremely careful, you know.

So anyway, you have to understand that the models are just the models. I always say live by models, you die by the models. That said, they're one of the greatest inventions of humankind ever exhibited.

They're sophisticated, complex, and they let us look into the future. You know, you just can't expect too much out of them either. But we're going to see this pattern come up, you watch.

So this pattern has been shown by the models. And it's been shown also that sometimes forecasters, human forecasters actually degrade the forecast by not following the models. So you have to be careful when you don't follow them.

(40:43) You got to have a really good reason. So that's my opinion on models.

(40:45) Charlie wants to know how much does the convergence zone around Everett affect Mount Baker?

Yeah, so the, so here's the convergence zone, just real quickly, everybody. You know, it is a zone of weather that happens typically after a weather front goes through. So the snow levels are reasonably low because it's colder air behind.

And what happens, the air comes off the Pacific, it hits the Olympic Mountain Range, like it's a rock in a stream. And it goes around, the air goes around the Olympic Mountain Range, and it reconverges or reconnects right around Everett. And creates a cigar-shaped band of moisture, thundershowers sometimes, but also snow into areas like Stevens Pass.

That's the typical conversion. Here's the convergence zone. Here's what happens, though.

We can have multiple convergence zones. There was one that can happen off the southern tip of Vancouver Island that can affect Mount Baker. There can be that one by itself, there can be multiple ones.

Here's another thing. The convergence zone oftentimes moves from Stevens and Snoqualmie down toward Crystal and White Pass. So you can get convergence zone moving.

Watch on the satellite, or really the radar, you can see it. It's a cigar-shaped band that's heavy rain that again is near Everett into the Cascades near Stevens. And sometimes it'll move.

The models understand these convergence zones. You can pick them up on the models, too. But they always happen after the weather front goes through.

So there can be multiple ones, too. There's not only one, there's more than one. And they can move around.

So don't get married to one. They'll be all over the place.

(42:30) Matt asks: who's got a better track record for calling big powder dumps? You or Cliff Mass?

Cliff is a good friend of mine.

We have collaborated on a few things. I think Cliff does a really good job. But Cliff's not a skier like me.

I think I have a little edge because I understand the snow like a few other forecasters do. I'm there all the time. I have seen all the conditions of the worst and the best.

But as far as big snow dumps, we all follow the models. But Cliff's a good guy. He has an excellent knowledge of Puget Sound weather and weather in western Washington.

(43:28) What do you think of the website snow-forecast.com?

I have heard of them and I've seen them. And I'm always leery of these really big ones because they're trying to do everything. And the guy that runs that, he's not going up to the Cascades.

He doesn't know what's going on. He has all the models and he's probably somewhere else. What I try to do is add value to the actual forecast by going up and saying, oh, tomorrow is going to be better because this will soften up.

Or guess what? This powder is going to settle on the south facing but the north facing is still really good. I try to put the nuances like that about the actual snow and stuff like that. Nowadays, people all have access to computer models and they have different ideas.

So I don't know about that site specifically.

But I would challenge anybody to out-forecast me in snow in the Cascades. Nobody can do it.

Several tried. I have bet them. But they have all lost.

(44:40) Tim says thank you for doing this. And how do the Rockies in the Canadian interior such as Banff, Lake Louise, generally get their moisture for their snowpack? Does the moisture come from storm systems coming in from the Pacific or generally come up from north in the Arctic?

That's a really good question. For the Rockies, some of their moisture is coming from the Pacific.

It's hard to believe. But if you've ever gone, it's not quite the Rockies, but if you've ever been to Schweitzer, you can see influence of the Pacific there. But even like Fernie in some places, those interior British Columbia near the Rockies.

So some of that moisture, again, it's storm dependent. So some of the moisture is coming from the Pacific and some of it is coming from lifted air that is cold and really kind of moisture starved air from the Arctic. Because the Arctic cold air doesn't have much moisture in it.

But it does have those storms do have some lift that cold air. So it's both is the answer. I don't know what the proportion is, but there's much more moisture available from the Pacific and it does it does go all the way to the to the Rocky sometimes.

(45:55) Silas says, hey, another forecast just came in for the Cascades and it is 50% less than earlier today.

I don't know what you're looking at. I don't know what you're talking about, because I didn't see that. Silas, where did that come from? Oh, wait, hang on.

(46:23) Dr. Zoidberg wants to know who would win at Jeopardy, you or Cliff Mass. Now you're really doing it.

Scrolling down unless Silas, Silas, you could unmute and tell us where you got that.

(46:38) Someone else says they came in late. What are your thoughts about Montana, Big Sky Bridger Bowl. I was just there high pressure keeping things sunny and dry. What might happen between now and March.

Yeah, so I mean, I think in the short range, they're going to get some snow like we are going to get and it's not going to be three feet, but it's going to improve, you know, beyond that, I would kind of lean toward less than normal snow there.

They're kind of in the bullseye of the dryness and warmth of El Nino. So I'd have to say that they may not fare as well. But in the short term, they'll get snow.

That's the thing. These short term patterns are superimposed on the bigger term patterns. And so that's I have always thought that you always have to go for the short term pattern.

And that's what will get you the goods. All right.

(47:37) Comment: maybe we get Cliff Mass here. Are models better than Cliff Mass?

Even Cliff can't outdo the models. They've done these studies now that forecasters, there's only one exception to that.

And that is in the real short term, maybe 12-18 hours. Humans can still beat the models. But beyond that, they can't beat the models.

The studies have been done. Cliff knows that too. So it's not like a big surprise.

(48:05) John says, Do you have the storm approach angles that produce a convergence zone at Crystal, Stevens, and the Pass?

Oh, good question. Yeah.

Well, you know, there is an angle. You can watch the winds at Hoquiam along the coast. I used to know these by heart, but I don't know.

I mean, I don't remember. I just watch for it to form. But it's usually after the front goes through.

It's a west-northwest wind, you know, so somewhere in that direction. What is that? 270 to 300, somewhere in there. Maybe 260 to 300, something like that on the wind rose.

And it does, you're right, it changes too. When the wind changes a little direction, it forces that convergence zone south, or a little bit north, or that other one forms. So you're right, you can get a sense of it by understanding the winds along the coast and seeing what they're doing.

So that's a good observation, whoever made that.

(49:14) Question: Since no one's really up to par yet If you had to get out, where would you go?

Nobody really has snow yet, but if you had to get out, where would you go? Okay, if I had to leave tomorrow, let's say I had my private jet, and leave tomorrow, I'd go to Grand Targhee. That's where I'd go. Or the other one would be Bella Coola helicopter ski operation, north of Whistler.

They've been getting a lot of snow. And if you don't know where that is, I've never been out there, but I've talked to a lot of people that have. It's quite a spectacular place, and they've gotten a lot of snow.

So those two places, before all this hits, that's where I'd be going. If I wanted snow, if I just want to ski and screw around, I'd go to Whistler or maybe somewhere local here.

(50:07) John says the last two throwaway seasons were 03-04 and 14-15. Were those El Ninos, and if they were, were they as strong as this season's cycle?

Okay, so it was 2005. And I'll get that. Oops, that's the wrong one.

So you're right, it was 2005. And here we go. 2005.

And here's El Nino. Is that five? There's three. So there were some El Ninos here, you know.

There's 2015 right up here. So there's El Nino here. And the 2005, I think, was right in here.

So those tend to be bad years. I mean, I can't deny it. The bad ones tend to be El Nino.

The good ones tend to be neutral or La Nina. But you know what? We get a lot more neutral and La Ninas than we do El Nino. El Nino really doesn't happen as often.

So that's why we have good snow in the Northwest. Because we get many more. Our normal year is good.

If we have La Nina, it sort of energizes our normal, which normal is good. So that's why we have good snow here. But El Nino doesn't always, but sometimes it tends to be our problem. You know, that's when we tend to get our problems.

(51:27) Rich says, what do you think of the weather info provided by the ski areas? For example, Stevens Pass?

Well, I mean, I don't know specifically what information. Generally, they're okay. I mean, they're going to spin it a little bit, you know.

NWAC has, you know, good data on their sites. They have excellent, one of the graphs I showed you, they'll show you if these guys are not telling the truth, they'll show you exactly hour by hour what's going on up there as far as winds and temperature and snow.

So the ski areas cannot, you know, exaggerate too much these days like they did in the old days. So I think my experience with all the ski areas in the Northwest, they're generally pretty honest.

If they're not, I'm going to call them on it. But they are. So I don't have a problem with it.

(52:27) One more question. Why was last year's snow in social like an El Nino pattern, yet it was a La Nina year?

Basically, it was like an El Nino. Like last year, California just got hammered. That's what you'd expect out of an El Nino year.

And we did okay, or we were great, but we did about average. And that's sort of what I would expect out of El Nino. But you know what, last year was La Nina.

This is, let me show you on the graph here.

This is La Nina last year. So California has one of their biggest snow seasons ever during La Nina.

And everybody predicted drier than normal. So this just shows you how the El Nino, La Nina is not a great predictor. Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn't.

But you know, it's not that great. Last year, great example. Didn't work at all.

(53:24) Okay, so I'm not sure if Silas's question was answered, but where the recent forecast was a 50% drop. So Silas, if you want to unmute. He saw that on the snow.

Silas: On the snow.com.

Larry: On the snow. Who listens to that? Come on, get it together.

Silas: Okay, so you still think we have two to three feet in the forecast for the next seven days?

Larry: I think one to three feet.I'll show you it. I'm sticking by it. There we go.

One next 10 days, one to three feet plus. Okay.

Silas: Great news.Thank you.

Larry: I'd pass on On the snow. You know, sometimes people, I mean, a freak thing can happen.

They could be right, but they're not. A lot of these online sites you find, they don't have a real person like watching it. And so you get whatever the model, you know, says.

And a lot of times nobody's, you know, doing a reality check on it, you know. So I'm not saying that's completely impossible.

Come on, it's the future. We don't know what's going to happen. But I'm just saying it's very likely minimum of one foot, but probably up to two and three feet. All right.

Silas: I want to believe.

Larry: You've got to believe brothers and sisters. You've got to believe.

(54:59) And someone says one to three is a huge range.

So yes, it's So here's why.

Okay, that's a good point. It's a good big range. Here's why we do these ranges.

Two reasons. One, different models say different things. Number two is the farther out you go, the less confidence.

Okay, so you have different confidence levels. That's why we give a range. Nobody's going to tell you exactly the models don't.

Nobody knows. This is why we have a range. Would you rather say, you know, I mean, it's just, this is, this is why how we forecast weather.

We forecast in ranges because of confidence level. I tried to show you this before. I have confidence levels of different things.

You know,

- I'm really confident of, it's going to snow and it's going to be cold,

- but I'm moderate confidence of timing and the specific Things about the storm and

- I have low confidence what's going to happen afterward.

So the different confidence is very important. You understand about weather forecast.

There's different confidence in different levels and different ranges of weather. That's extremely important. Every forecast does not have the same confidence level.

(56:11) All right. Let me have my heart attack and I'll go to sleep.

Thank you, everyone. I really appreciate really great questions. I gotta say I love getting the questions.

It makes me think And I'm glad I could answer them best I could. And let's get ready. We're going to have some snow.

If, if that slide you see (above) right now, if there isn't something like that. Maybe not exact but something like that. I will be incredibly shocked.

All right, that's something like that's going to happen might not be exact, but it's something like I put the there's a link that I put in chat for the blog post that will have the recording and the transcript and the slides. So that is in there. And I'll let Larry sign off and I'll just say thank you.

And I will pick two winners for each will get a $100 gift card for woolly apparel, which is one of our amazing sponsors and I will pick two people at random and email you in about 20 minutes. Thank you, everyone. Thank you, Andrea.

And let's, let's see this thing develop. Meanwhile, please support our sponsors Zeke's Pizza is another one we didn't mention and Alpine PT. Great guys.

If you have any kinks in your head or anything. So they've helped me out too. But that pizza is good too over at Zeke's.

All right. Bye. Thanks, Larry.